Without doubt, the Automobile ranks among the two or three most important inventions of our age. The car has determined the shape of our cities and the routine of our lives, made almost every inch of our nation easily accessible to everybody, ribboned our country with highways, cluttered the landscape with interchanges, gas stations, parking lots, drive-ins, and auto junkyards, and covered over 50,000 square miles of green with asphalt and concrete Considering that there is now one automobile in this country for every two persons (compared to, say, China, with over 14,500 persons per car), it’s certainly easy to agree with a writer who described the American as a “creature on four wheels.”

The technological revolution that has produced our mobile, car oriented society has taken place almost entirely in the last seventy or eighty years. But the idea of a self-propelled vehicle, with more modest accoutrements, indeed-had been on man’s mind for centuries before the first automobile cranked into gear. As long ago as the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon predicted the use of vehicles propelled by combustion, and in 1472, a Frenchman named Robert Valturio described a vehicle combining wind power and a cogwheel system for propulsion.

To the owner of an Automobile 70 years ago, air conditioning, power steering and a stereo would probably seem fit only for the most expensive of limousines. Today, we’re apt to find them in many ordinary family cars. If we insist on comfort as much as speed and reliability in the automobiles we drive, it’s not without good reason: in the age of the Automobile, an American can spend up to 10 or 15 percent of his waking hours in the well-appointed confines of his home away from home, the car.

If, in 1600, you happened to be walking along a Dutch canal, you might have been surprised to see a two-masted ship bearing down on you. Not in the canal-on the road. There was one such ship that was said to have reached a speed of twenty miles per hour while carrying twenty-eight fear-stricken passengers. In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci had envisioned some sort of self-propelled vehicle; and some Dutchman, quite naturally, had modeled such a vehicle after a sailing vessel.

About 1700, a Swiss inventor mounted a windmill on a wagon. It was hoped that as the windmill wound up a huge spring, the vehicle would lope along under its own power.

In the early eighteenth century, another Frenchman designed a machine run by a series of steel springs, similar to a clock movement, but the French Academy had the foresight to declare that a horseless vehicle “would never be able to travel the roads of any city.”

No single man can be termed the inventor of the automobile.

Rather, advances on motor cars were made by many men working in various countries around the same time. But credit for the first mechanically propelled vehicle is generally given to the French engineer Nicholas Cugnot, who in 1769 built a three-wheeled steam-propelled tractor to transport military cannons. Cugnot’s machine could travel at speeds of up to two-and-a-half miles per hour, but had to stop every hundred feet or so to make steam.

Through much of the eighteenth century, steam-driven passenger vehicles-both with and without tracks-were in regular operation in England. The early steam engine, however, was found to be impractical on ordinary roads, for it required great engineering skills on the part of the driver. Numerous fatal accidents stiffened resistance to the new machines, and beginning in 1830, Parliament passed a number of laws greatly restricting their use. One such regulation, called the Re( Flag Law, stipulated that horseless cars must be preceded by a person on foot with a red flag in hand, or a red lantern at night, to warn of the car’s approach. Another law limited the speed of horseless vehicles to a blinding four miles per hour. The limit was not raised until 1896, when English motor club members celebrated with an “emancipation run” from London to Brighton, initiating what was to become an annual event.

These early restrictions naturally limited interest in automotive research in England. Other sources of power were investigated elsewhere. Over the latter years of the nineteenth century, various electric cars were introduced with some frequency, but these never quite caught on with the public because they had to be recharged regularly. Most work on the internal-combustion engine was performed on the continent, especially in France and Germany. The internal-combustion engine, like the auto itself, had no single inventor. But in 1885, Gottlieb Daimler of Germany became the first to patent a high-speed four-stroke engine.

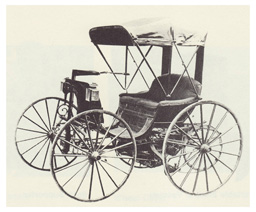

Around the same time, Karl Benz, another German, was building an internal combustion tricycle that could reach a speed of ten miles per hour. The general public remained largely unimpressed. A German newspaper, reporting on Benz’s work, asked the question: “Who is interested in such a contrivance so long as there are horses on sale?”

Daimler and Benz worked independently for years, but later joined to form what is now the Mercedes-Benz Company-the name Mercedes having been borrowed from the daughter of a Daimler associate.

The first practical gasoline powered car with a modern type chassis and gears was the work of a Frenchman named Krebs, who designed the Panhard in 1894. In the early years of the industry, France led the world in automobile production. The still-flourishing Renault Company was founded before 1900. But around the turn of the century, Americans began to take the lead in automotive innovation.

The first successful internal combustion car in the United States was the work of the Duryea brothers, Charles and J. Frank, bike manufacturers from Springfield, Massachusetts. The Duryeas had read of Karl Benz’s work in Germany, and built their first car in 1893. Two years later, the brothers formed the Duryea Motor Wagon Company, the first automobile manufacturing firm in the nation. They later went on to win one of the most important races in automobile history.

Racing and sport motoring were then considered the primary uses of the automobile. Few people could see the future of the car as a common means of practical transportation. The first Automobile race ever held was won by a car that was powered by a steam engine. On June 22, 1894, Paris was bubbling with excitement as twenty horseless carriages lined up for the 80 mile race from Paris to Rouen and back again to the big town.

Could these newfangled things run at all? And if they did, would they prove as fleet and as durable as a few changes of horses?

Less than five hours later, a De Dion Bouton lumbered down the boulevards of gay Paree. The steamer had covered the distance at the daredevil rate of seventeen miles per hour.

The first auto race in America was held on Thanksgiving Day, 1895, over a snowy fifty-five mile course stretching from Chicago to Waukegan, Illinois. Sponsored by the Chicago Times-Herald, the event included about eighty entries. But only six vehicles managed to leave the starting line. Only two finished-the victorious Duryea, and a rebuilt electric Benz that had to be pushed over a considerable part of the route. The victory of the gasoline powered Duryea did much to establish the internal-combustion vehicle as the car of the future.

At the time, American cities were certainly in desperate need of horseless carriages, and horseless streets. Around the turn of the century, New York City’s equine helpmates were depositing some 2.5 million pounds of manure and 60,000 gallons of urine on the streets each day!

American engineers and inventors rose to meet the challenge with great advances in automotive technology in the later years of the nineteenth century; and in 1899, over 2,500 cars were produced by thirty different American companies. By 1904, there were over 54,500 cars on the roads here. But even then, poor roads and high costs made the Automobile chiefly a sporting vehicle. It remained for American industrial genius to bring the car within reach of the average citizen.

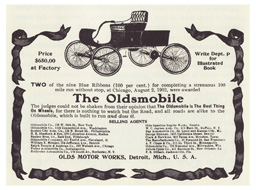

Henry Ford is usually credited with introducing mass-production techniques to automobile manufacture, but Ford actually adapted innovations made earlier by Ransolm E. Olds. Olds was but thirty years old when he designed his first internal combustion vehicle in 1897.

Later, Olds was forced to seek financial help from a friend, a scrap merchant in Detroit, who agreed to advance the needed capital if Olds would locate his plant in Detroit, then a city of less than 300,000 people. By 1902, Olds was turning out 2,500 cars annually with assembly-line techniques, and the “Motor City” was born. Today, the Detroit-Flint corridor in Michigan produces about one-fourth of all American cars.

Henry Ford began his motor company in 1903 with capital of only $28,000, twelve workers, and a plant only 50 feet wide. Additional funds were supplied by the Dodge brothers, themselves auto manufacturers, and the Dodges’ initial $20,000 investment was eventually worth $25 million. Soon afterward, Ford improved on Olds’s mass-production ideas and introduced the conveyor-belt assembly line. Ford’s first successful mass-produced car was the Model N, brought out in 1906 for $500. (From the very beginning, Ford used letters of the alphabet to identify his models.) But the car that made Henry famous was the Model T.

Preparation for the Model T’s production brought Ford so close to bankruptcy that he had to borrow $100 from a colleague’s sister to pay for the car’s launch. That $100, by the way, was eventually worth $260,000 to the generous donor. The first “Lizzie” rolled off the line in 1908, with a four-cylinder, 20-horsepower engine capable of speeds of forty miles per hour. It carried a price tag of $850.

Mass-production innovations continued to lower the price of the Lizzie. In 1916, a new model sold for just $360! Each vehicle finished its turn around the assembly line in just ninety minutes, compared to the earlier day and a half assembly-line run.

Today, most plants can turn out fifty to sixty cars an hour, and till Chevrolet plant in Lordstown, Ohio, the nation’s most modern, can produce over 100 vehicles an hour.

Sales of the Model T rose to 734,811 in 1916, accounting for half of all American-car production. Eventually some 15 million Lizzies were produced before the car was discontinued in 1927. From 1915 on, the Ford Company offered its prize automobiles in any color, so long as it is black.”

In 1908, there were over 500 car companies in the United States, but that year marked the beginning of General Motors’ eventual domination of the automobile market. The corporation was largely the work of William Crapo Durant, the millionaire grandson of a Michigan governor. Durant gained control of his first car company, Buick, in 1904, and moved his plant to Flint, Michigan. In 1908, Durant took over the Olds Company, although Ransolm Olds himself had left the firm in 1905 to form the Reo Company. Durant now began to absorb a number of ailing car and accessory companies under the corporate umbrella of General Motors. The Cadillac Company-named for Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, the founder of Detroit-joined GM in 1909. Durant even approached Ford with an offer to join General Motors, but Henry turned him down.

The roller coaster career of W.C. Durant took a turn for the worse shortly after General Motors was formed, and he eventually lost control of the corporation he had founded. Durant’s new car firm, the Chevrolet Company, named after a race driver who had designed engines for Durant, was such a success that the new leaders of GM were forced to take Durant, and Chevrolet, into the firm. By 1918, Durant was again at the helm of the corporation. But the founder of what is presently the largest manufacturing corporation in the world, with sales of $35 billion in 1975, declared bankruptcy in 1936, claiming over a million dollars in debts and assets of just $250, the clothes on his back!

The first decades of this century saw bankruptcy and merger greatly reduce the number of American car firms. In 1920, Walter Chrysler, a former vice-president at General Motors, joined the Willys-Overland company, once the number 2 car producer after Ford, and laid the groundwork for the Chrysler Corporation. Chrysler absorbed Maxwell-Chalmers and the Dodge brothers’ company, and introduced the Plymouth in 1929. The Lincoln Company became part of the Ford Corporation in 1921, and the Mercury was introduced in 1939.

The Studebaker and Packard, both introduced before 1902, eventually merged, and the Nash Company, founded by Charles Nash, who had replaced Durant at General Motors-joined the Hudson Company in the 1950’s to form the American Motors Corporation. As early as 1914, 75 percent of all American cars were manufactured by the ten largest companies.

The Rolls-Royce Corporation was founded in 1904 by two Englishmen named, you guessed it, Rolls and Royce.

The familiar Volkswagen “beetle” was first produced in 1938. By the 1950’s, Volkswagen was the largest car producer in Europe; and in 1972, the “beetle” surpassed the Model T in total sales for a single model, with over 15 million sold throughout the world.

The United States has been the leader in automobile production for many years. Over a million cars were produced here in 1916, and over 3 million in 1924, when there were some 15 million cars registered in America. In 1952, about 4 million American passenger cars rolled off the line, ten times the number produced by the second-rank ing nation, Great Britain. At the time, there was a car on the road here for every 3.5 persons alive, compared to, for example, one car per 564 persons in Japan. The second-ranking nation in car use was, surprisingly, New Zealand, with six persons for each car.

American dominance of the automobile market has slipped some what in recent years, yet the United States still ranks first in total production, with 6.7 million passenger cars turned out in 1975. Japan ranked second that year with 4.5 million cars, followed by West Germany and France with just under three million each, Great Britain and Italy with about 1.4 million each, Canada with one million, and the Soviet Union with 670,000.

What is the most popular car in America? For years it’s been the Chevrolet. In 1975, 1.6 million new Chevies left the assembly line, while the Ford ranked second with 1.3 million cars, followed in order by the Oldsmobile, Buick, Pontiac, Plymouth, Mercury, Dodge, and Cadillac. Among American auto manufacturers, General Motors was far and away the leader, with 3.6 million cars produced; Ford was second with 1.8 million, Chrysler third with 900,000, and American Motors fourth with 320,000.

In 1978, there were about 107 million passenger cars registered throughout this country, and 125 million licensed drivers. Car registration began here in 1901, in New York State. The first license plates appeared in France in 1893.

England’s first license plate, Al, was purchased in 1903 by Lord Russell, after an overnight wait outside the license bureau office, and that plate was reportedly sold to a collector in 1973 for $35,000! As late as 1909, driving licenses were required in only twelve American states, when there were few traffic laws of any kind. The first modern traffic light, in fact, did not appear until 1914, on Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio. And in England driving tests were not required for would-be drivers until 1935!

The first traffic accident in the United States was recorded in 1896 when a Duryea Motor Wagon collided with a bicycle in New York City, sending the cyclist to the hospital and the driver to jail. Three years later, a sixty-eight-year-old real estate broker named Henry Bliss became the first American to die as the result of an auto accident, when he was run over while stepping from a New York streetcar. By the early 1920’s, traffic fatalities were already topping the 20,000 mark annually-not to mention an estimated 700,000 auto injuries each year.

In the mid-1950’s, close to 3 million Americans were killed or injured each year in automobile accidents-about 570 deaths for every 10 billion miles driven, compared to fourteen deaths for every 10 billion airplane miles, thirteen deaths for the bus, and just five for the train.

But Americans are far from the world’s most reckless drivers. That honor belongs to the Austrians, who in a recent year suffered 386 auto deaths per one million population. That year, drivers in West Germany, Canada, and Australia also suffered more fatal accidents than their American counterparts, with the United States in fourth place with 272 deaths per million persons. The lowest rate among major car-using nations belonged to Mexico, with just 83 deaths per million persons.

Surprisingly enough, the death rate per vehicle mile has actually declined here since 1941, due in large part to the proliferation of di vided highways. The Interstate Highway System, the largest single construction job ever undertaken by man, will, when complete, include about 42,500 miles of divided highway, accommodating an estimated 25 percent of all United States traffic. The system was 80 percent complete in the mid-70’s.

Automobile design and usage have changed a great deal since the days of Daimler, Benz, and Duryea, but almost all cars, past and present, compact and luxury, have one thing in common: the internal-combustion engine. (A present exception is the Mazda, which operates with a rotary, or Wankel engine.) The internal-combustion engine converts heat generated by the burning of gasoline to the motive power required to turn the car wheels.

Basically, the internal-combustion engine works like this: fuel and air first mix in each cylinder of the engine. The piston in the cylinder, rebounding from its previous stroke, compresses the fuel and air mixture. At this point, a hot electric spark ignites the compressed mixture. The rapid combustion of the gasoline and air mixture speeds up the motion of their molecules, increasing the pressure they exert on the top of the piston. This pressure forces the piston down the cylinder.

Each downward stroke of the piston turns the crankshaft, which in turn spins the drive shaft. The drive shaft turns the gears in the differential, the gears turn the rear axle, and the axle rotates the rear wheels. Unless the car is equipped with four-wheel drive, the front wheels are not connected to the engine-driven mechanism.

A car runs more smoothly at night or in damp weather simply because the air is cooler, not because it contains more oxygen; the amount of oxygen in the air is constant. Cool air is more dense than warm air; and therefore, an engine takes in a greater weight of air when it is damp and chilly. This accounts for the increased power and the freedom from engine knock which so many motorists notice when they drive at night or in the rain.

Most cars today are equipped with either a 4, 6, or 8-cylinder engine-but a 1930 Cadillac was powered by a sixteen-cylinder engine! And speaking of Cadillacs, the largest automobile ever constructed was a special limousine built for King Khalid of Saudi Arabia in 1975, measuring twenty-five feet, two inches in length and weighing 7,800 pounds.

The largest car ever produced for regular road use was the 1927 “Golden Bugatti,” which measured twenty-two feet from bumper to bumper. Only six of these cars were made, and some of these survive in excellent condition.

Automobiles over twenty feet in length are built more for comfort than speed, of course, but compared to the earliest automobiles even the most cumbersome of today’s limos are virtual speed demons. The first auto race in Europe, held in France in 1895, was won by a car averaging but fifteen miles per hour. The Duryea brothers’ car won the Chicago-to-Waukegan race that year with an average speed of only seven-and-a-half miles per hour. By 1898, the record automobile speed stood at a mere 39.3 miles per hour. A little over sixty-five years later, Craig Breedlove became the first person to drive a car over a mile course at an average speed in excess of 600 miles per hour. The record for the highest speed ever attained by a wheeled land vehicle was set on the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah in 1970, when Gary Gabelich drove a rocket-engined car at an average speed of 631 miles per hour over a distance of one kilometer.

With the current fifty-five mile-an-hour limit on all American roads, you certainly won’t need such horsepower. But if it’s sheer velocity you’re interested in, you might take a look at the Lamborghini Countach or the Ferrari BB Berlinetta Boxer, the fastest regularly produced cars now available, which can both reach speeds of 186 miles per hours.

If price is more important to you than speed, you might want to test -drive a Mercedes 600 Pullman, the most expensive standard car now on the market. One of these six-door beauties will set you back $90,000-less your trade-in, of course. And if used cars are your preference, you might be interested in a Rolls-Royce Phantom, once owned by the Queen of the Netherlands, that sold in 1974 for a record $280,000!

Speaking of used cars, the most durable car on record was a 1936 Ford two-door model that in 1956 logged its one-millionth mile-with the odometer showing zero miles for the eleventh time. Today, a car is considered well into old age by the time it reaches 75,000 miles.

But surely, the most incredible automobile record ever achieved belongs to Charles Creighton and James Hargis who, in 1930, drove a Ford Model A roadster from New York City to Los Angeles without stopping the engine once. The two men then promptly drove back to New York, completing the 7,180-mile round-trip in forty-two days.

Oh, one more thing: on both coast-to-coast journeys, the car was driven exclusively in reverse!