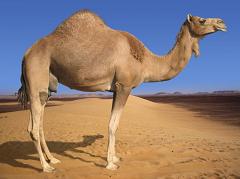

Despite what you might have heard, camels don’t really store water in their humps.

Instead, the humps are big chunks of fat. Sure, it looks funny, but it’s a system that works. In the desert camels may have to go for days and weeks without food, so the humps act as a storehouse of energy.

Why isn’t a camel’s fat distributed all over its body, as with almost all other animals? Ask any polar bear, and he’ll tell you that fat also makes a really good insulating jacket.

That’s why polar animals tend to look more like sumo wrestlers than ballerinas.

As you can imagine, the last thing a camel wants in the desert is a layer of warm fat all over, so it’s evolved to a point where it’s localized its fat into one, if Arabian, or two, if Asian, high-cholesterol lumps on top of its back.

Other unusual heat-coping features keep camels the preferred ship of the desert. For starters, their kidneys are designed to absorb an unusual amount of moisture in their urea.

Also, their body temperature rises from 95 ° F at night to more than 104° F during the heat of the day, not an unusual thing with fish and amphibians, but almost never seen in mammals.

Only at the higher temperature do camels begin to sweat, and when they do sweat, they lose moisture evenly from all tissues of their bodies, instead of just from the blood like most mammals.

This allows a camel to lose 40 percent of its body weight in water before its life is endangered. It makes up this loss with binge drinking, staggering into an oasis and sucking down as much as fifty gallons at a time.

A Camel Walks into a Bar.